Chapter 12 pertains to Computability Theory, which attempts to distinguish between problems that are computable and those that are not. Focusing on decision problems, this distinction is between languages that are decidable (aka recursive) vs. undecidable (not recursive). The class of undecidable languages can be further partitioned into those that are "semi-decidable" (recursively enumerable (RE), but not recursive) and those that are not even RE.

Complexity theory, on the other hand is concerned with the resource requirements of algorithms that decide languages. These resources are time and space (amount of memory). Linz focuses upon time complexity and says little about space complexity.

Definition 14.1: A Turing machine decides a language L in time T(n) if, for every w ∈ Σ*, M halts in ≤ T(|w|) moves with its verdict (ACCEPT or REJECT). (Recall that if M is nondeterministic, w ∈ L(M) is deemed to be the case iff there is at least one sequence of moves that leads to an ACCEPT verdict, even if other sequences of moves lead to a REJECT verdict.)

Definition 14.2:

A language L is a member of DTIME(T(n)) if there exists a

deterministic multi-tape Turing machine that decides L in time O(T(n)).

A language L is a member of NTIME(T(n)) if there exists a

nondeterministic multi-tape Turing machine that decides L in time O(T(n)).

Of course, DTIME(T(n)) ⊆ NTIME(T(n)), because deterministic TM's are special cases of nondeterministic TMs. Also, if T1(n) ∈ O(T2(n)) (which is to say that, as n grows, T1(n) grows no more quickly than does T2(n)), we also have DTIME(T1(n)) ⊆ DTIME(T2(n)).

In the realm of polynomial versions of T:

Theorem 14.3: for every integer k≥1, DTIME(nk) ⊂ DTIME(nk+1).

Notice that the inclusion is proper. It follows that the hierarchy of time complexity classes is infinite, even among those T that are polynomials.

In Section 14.3, Linz makes connections between this hierarchy and the Chomsky hierarchy of languages. He notes that LREG ⊆ DTIME(n), which is to say that for every regular language there is a linear-time algorithm that decides it. (This is not surprising, as every regular language has a DFA that describes it, and we can simulate the computation of a DFA on a given string in time proportional to the length of that string, as following each transition in the DFA takes constant time.)

Also of note is that LCF ⊆ DTIME(n3), which is to say that for every context-free language there is a cubic-time membership algorithm. This follows from the existence of the CYK algorithm. Also, LCF ⊆ NTIME(n). This makes sense, as the application of a nondeterministic PDA to an input string can be carried out in linear time.

However, Linz points out that the connection between the language classes in Chomsky's hierarchy and those in the DTIME() and NTIME() hierarchies is not particularly clear.

What seems more interesting and fruitful is to consider the classes

|

and |

|

P is the set of all languages that are accepted by polynomial-time deterministic Turing machines. Meanwhile, NP is the set of all languages that are accepted by polynomial-time nondeterministic Turing machines.

Of course, P ⊆ NP (because deterministic TMs form a subset of nondeterministic TMs), but no one knows whether this inclusion is proper! That is, no one knows the answer to the question "Is P = NP?"

It turns out that most practical problems of interest that are (known to be) in P tend to be in, at worse, DTIME(n4). Thus, even though all but very small instances of a problem that is in, say, DTIME(n100) —but not in DTIME(n99)— would take an unrealistic amount of time for a computer to solve, we informally apply the term tractable to all problems in P, to distinguish them from the intractable problems (i.e., those that are not members of P). (Such problems would be ones for which any algorithmic solution would have a running time that grows more quickly than any polynomial. Examples are problems that are in DTIME(2n) but not in P.)

In Section 14.5, Linz presents some examples of problems in the class NP that are not known to be in P. Indeed, these problems are among the "hardest" problems in NP; such problems are referred to as being NP-Complete. (A more detailed explanation is found below.)

The problem is this: Given a CNF expression, does there exist a truth-assignment to the variables that "satisfies" the expression (i.e., makes it evaluate to true)?

The obvious deterministic algorithm iterates through every possible assignment of truth-values to the variables in an attempt to find one that makes the expression evaluate to true. If one is found, the algorithm outputs YES; if none is found, it outputs NO. Because there are 2m distinct truth-value assignments to the m variables, this takes, in the worst case, exponential time. Better deterministic algorithms are known, but none that run in polynomial time.

Now consider a nondeterministic algorithm for this problem that "guesses" a truth-assignment for the variables, evaluates the expression with respect to that truth-assignment, and outputs "YES" (respectively, "NO") if the result comes out to true (resp., false). Of course, if at least one satisfying truth-assignment exists, there is a "correct guess" that leads to a YES output. If there is no satisfying assignment, there is no correct guess and thus all possible executions of the algorithm produce NO. (Remember, a nondeterministic decision algorithm is defined to accept a string iff at least one possible computation on that string results in it printing YES, even if other computationss result in the printing of NO.)

Constructing a "guessed" truth assignment and then checking to see whether the expression yields true with respect to that assignment takes only polynomial time. Hence, SAT ∈ NP.

No polynomial-time deterministic algorithm is known for this problem. A solution that takes time proportional to n! (or slightly worse) is to generate every possible permutation of the vertices (of which there are m! if there are m vertices) and, for each one, determine whether it corresponds to a path in the graph.

The nondeterministic version of the algorithm is this:

A polynomial-time nondeterminstic solution is this:

As far as anyone knows, there is no deterministic polynomial-time algorithm for this problem.

Remarkably, it turns out that the problems described above, and many others, are all related by the fact that, if any one of them is a member of P (i.e., is solvable by a polynomial-time deterministic algorithm), then all of them are in P and, moreover, P = NP! Problems of this kind are said to be NP-Complete.

The key concept used in showing a problem to be NP-Complete is that of polynomial-time reducibility.

Definition: A language L1 is said to be polynomial-time reducible to language L2 if there exists a polynomial-time deterministic algorithm by which any string w1 (over the alphabet of L1) is transformed into a string w2 (over the alphabet of L2) such that w1 ∈ L1 iff w2 ∈ L2.

As a trivial example of a polynomial-time reduction, consider the languages L1 = {w ∈ {0,1}* | w has more 0's than 1's } and L2 = {w ∈ {0,1}* | w has fewer 0's than 1's }.

A polynomial-time reduction of L1 to L2 is this: Given w1, produce w2 by flipping each bit (i.e., replacing each occurrence of 0 by 1 and each occurrence of 1 by 0). Clearly, w1 has more 0's than 1's iff w2 has fewer 0's than 1's, which is to say that w1 ∈ L1 iff w2 ∈ L2, as required.

Reduction from SAT to 3SAT: A more interesting polynomial-time reduction is sketched by Linz in Example 14.9, where he claims that any CNF expression E can be transformed into a 3-CNF expression E' (a CNF expression in which every clause has exactly three distinct literals) such that E is satisfiable iff E' is satisfiable. The reduction goes like this:

Let E = C1 ∧ C2 ∧ ... ∧ Cm be a CNF expression, where each Ci is a clause, and hence of the form l1 ∨ ... ∨ lk, where each li is a literal (meaning either a variable x or negated variable ¬x).

The reduction replaces each clause C in E by one or more clauses, like this: Suppose that C = l1 ∨ ... ∨ lk.

For example, the four-literal clause l1 ∨ l2 ∨ l3 ∨ l4 would be replaced by

Meanwhile, the seven-literal clause l1 ∨ l2 ∨ l3 ∨ l4 ∨ l5 ∨ l6 ∨ l7 would be replaced by

For this to be a valid polynomial-time reduction, these two conditions must be met:

Now we address this second point. First we argue that, for each clause C in E, the conjunction of clauses C' that replaces it in E' is satisfiable iff C is satisfiable. More precisely,

Lemma:

Corollary: C is satisfiable iff C' is satisfiable.

Proof:

Case 1: C has one literal (i.e., C = l1).

As specified above

C' =

(l1 ∨ z1 ∨ z2) ∧

(l1 ∨ ¬z1 ∨ z2) ∧

(l1 ∨ z1 ∨ ¬z2) ∧

(l1 ∨ ¬z1 ∨ ¬z2),

which is logically equivalent to C = l1

(and thus the lemma holds in this case).

(Indeed, the truth-assignments that satisfy C' are precisely those that map

l1 to true.)

Case 2: C has two literals (i.e., C = l1 ∨ l2). As specified above, C' = (l1 ∨ l2 ∨ z1) ∧ (l1 ∨ l2 ∨ ¬z1), which is logically equivalent to C = l1 ∨ l2 (and thus the lemma holds in this case). (Indeed, the truth-assignments that satisfy C' are precisely those that map at least one of l1 and l2 to true.)

Case 3: C has three literals. As specified above, C' = C, and thus the lemma holds in this case.

Case 4: C has more than three literals (i.e., C = l1 ∨ l2 ∨ ... ∨ lk, where k > 3). Recall that

First we show item (1) from the lemma. Suppose that there is an assignment that satisfies C. Such an assignment must make at least one of the literals in C true, say li. Then extend that truth-assignment (to include the z's) by mapping to true each of z1 through zi-2 (i.e., all of which have "positive" appearances in clauses prior to the clause in which li appears) and mapping to false zi-1 through zk-3 (i.e., all the z's having "negated" appearances in clauses coming after the one in which li appears. Such an assignment makes true all the clauses in C' and hence is a satisfying assignment for C'.

Now we show item (2) from the lemma, using proof by contradiction. Assume, contrary to what (2) says, that there is a truth-assignment that satisfies C' which, when restricted to the variables in C (i.e., the non-z variables), fails to satisfy C. Such an assignment makes true every conjunct of C' while making false every literal in C. If we were to partially evaluate C' under this assignment, applying only that part of the assignment relevant to the non-z variables, every occurrence of an li would simplify to false. Plugging in false for every such occurrence and simplifying the resulting expression (using the fact that p ∨ false ≡ p), we get

Now consider that part of the assignment relevant to the z-variables.

To satisfy the first clause in this formula, z1 must be mapped to

true. But then the only way to satisfy the second clause is to map

z2 to true. But then the only way to satisfy the third

clause is to map z3 to true. Repeating the same reasoning

again and again (through the next-to-last clause in C'), each of z4

... zk-3 must be mapped to true. But that leaves the

last clause, (¬zk-3) having value false, and thus

this assignment fails to satisfy C'. This is a contradiction! Hence,

our assumption is false, thereby showing that, in this case, item (2)

of the lemma holds.

End of proof.

Now consider E and E' as a whole. We must show that E is satisfiable iff E' is satisfiable. (So far all we have proved is that each clause C in E is satisfiable iff its replacement C' (which is a conjunction of clauses) within E' is satisfiable.)

For implication from left to right (if E is satisfiable, then so is E'), assume that E is satisfiable and consider any assignment that satisfies E. The same assignment, augmented by assigning values to all the z-variables in E', in the manner described above, produces a satisfying assignment for E'.

For implication from right to left (if E' is satisfiable, then so is E), assume the contrary. That is, assume that there is a truth-assignment that satisfies E' but fails to satisfy E. Any such assignment, restricted to the variables appearing in E (i.e., the non-z variables), must falsify at least one of the conjuncts Cj of E while at the same time truthifying the conjunction of clauses C'j that replaced Cj in constructing E' from E. But the corollary to the lemma above says that this is not possible! Hence, the result is proved.

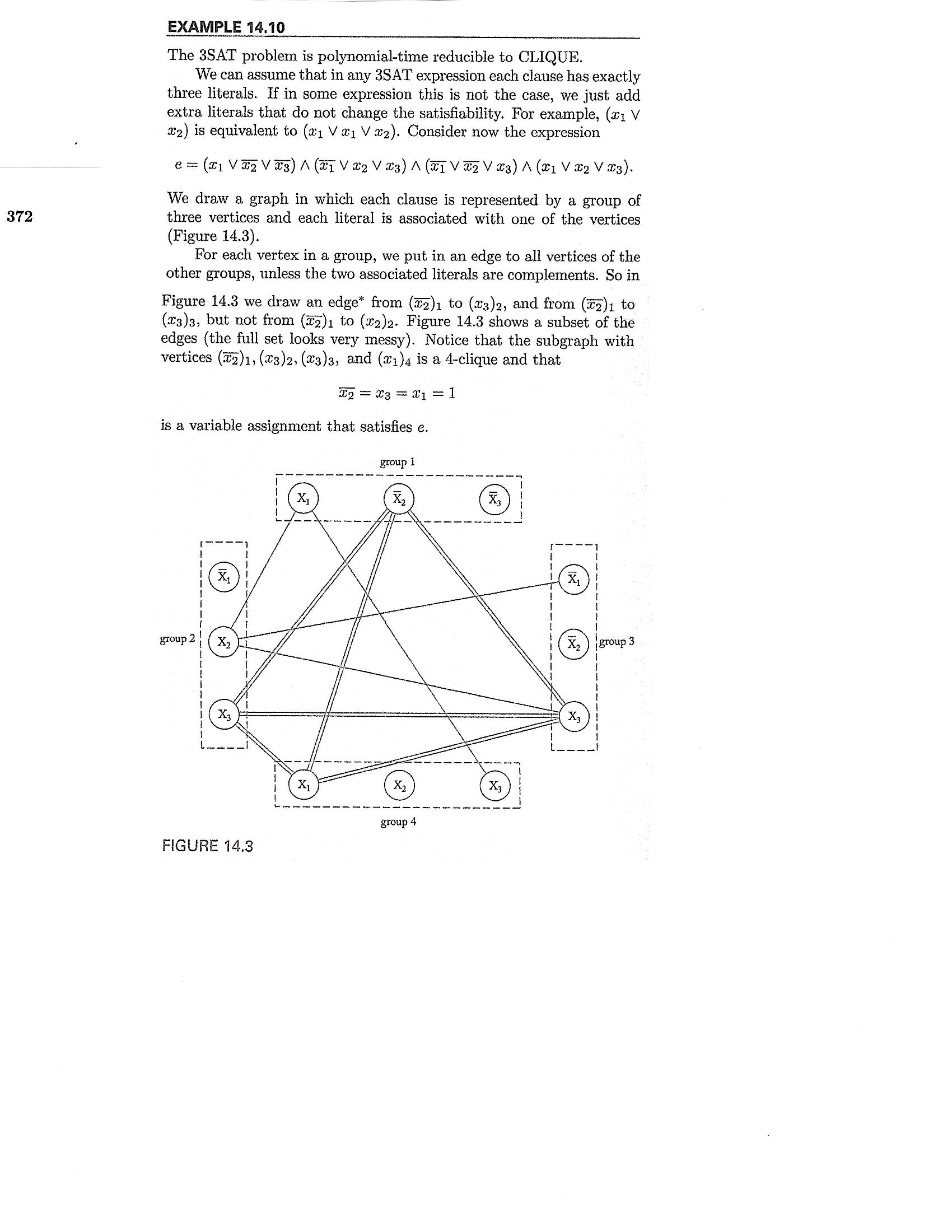

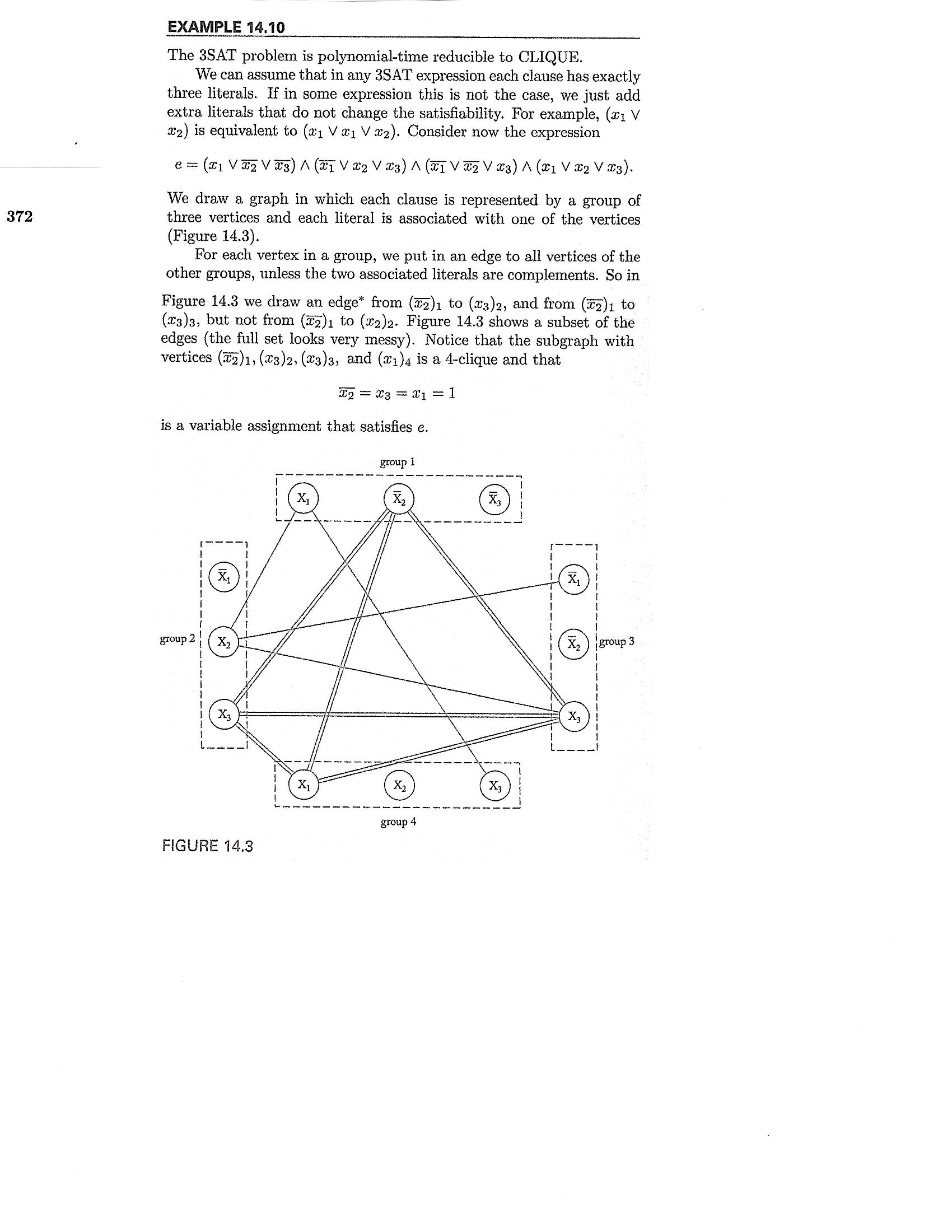

Reduction from 3SAT to CLIQUE: Recall that the Clique problem is this: Given an undirected graph G and a positive integer k, does G have a clique of size k? A clique is a set of vertices all of which are connected by edges to all the others in the clique. In Example 14.10 (see figure below), Linz describes a polynomial-time reduction from 3SAT (Given a 3-CNF expression, is it satisfiable?) to CLIQUE. In Figure 14.3 (also in figure below), he illustrates the reduction using an example.

|

Claim: The reduction is such that the given 3-CNF formula F is satisfiable if and only if the graph G constructed from it has a clique of size equal to the number of clauses in F.

Proof: First we show implication from left to right (i.e., if F is satisfiable, then G has a clique of size k, where k is the number of clauses in F). Take any truth assignment that satisfies F. Such an assignment makes true at least one literal in each clause. Each clause C has an associated "group" of three vertices in G, with each of those vertices being identified with one of the literals in C. In each of the k groups of vertices, choose one vertex that is identified with a literal that the assignment makes true. This set of k vertices forms a clique!

Now consider implication from right to left (i.e., if G has a clique

of size k, then F is satisfiable).

First, G cannot have a clique of size more than k, because no two

vertices in the same "group" are connected by an edge, and hence at

most one vertex from each group, of which there are k, can be in any

clique. It follows that the only way for G to have a clique of size k

is for it to contain exactly one vertex from each group. Suppose that

such a clique exists. Each vertex in the clique is identified with a

literal from F. Choose an assignment that makes true every such literal.

This is possible because no two vertices representing "opposing" literals

can be in the clique, because no two such vertices are connected by an edge.

Such an assignment satisfies F, because it ensures that every clause has at

least one literal that the assignment makes true.

End of proof.

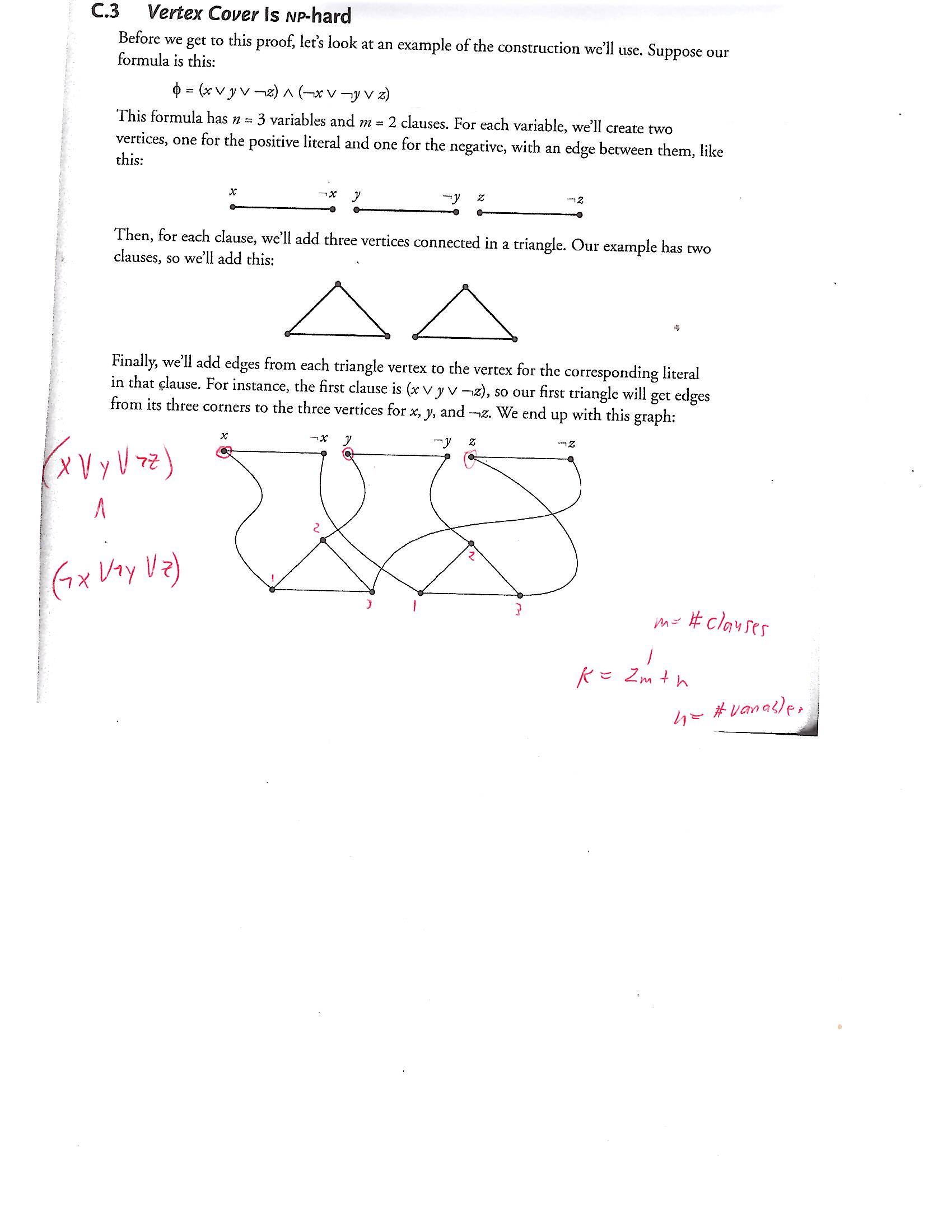

Reduction from 3SAT to VERTEX COVER: The figure below illustrates, via an example, a polynomial-time reduction from 3SAT (Given a 3-CNF expression, is it satisfiable?) to VERTEX COVER. The VERTEX COVER problem has as inputs an undirected graph G and a positive integer k, the question to be answered being

"Does there exist a vertex cover in G of size k (or less)?"

A vertex cover of a graph G is a subset V' of its vertices such that at least one endpoint of every edge in G is a member of V'.

The construction from 3SAT has the property that the given 3-CNF formula F is satisfiable iff the constructed graph has a vertex cover of size 2m+n, where m is the number of clauses in F and n is the number of distinct variables mentioned in F.

|

The construction is as follows:

Claim: This reduction is such that the given 3-CNF formula F is satisfiable if and only if the graph GF constructed from it has a vertex cover S of size k = 2m + n, where n is the number of distinct variables mentioned in F and m is the number of clauses in F.

Proof: First we show implication from left to right (i.e., if F is satisfiable, then G has a vertex cover of size 2m + n). Consider any truth-assignment that satisfies F, and apply that assignment to the vertices of GF, so that each vertex is mapped to either true or false in accord with the literal in F to which it is associated.

We observe that each edge connecting two base vertices to each other has exactly one endpoint that maps to true. Also, each triangle includes at most two vertices that map to false (because otherwise the corresponding clause in F would not be truthified by the assignment).

Let S be the set of vertices that includes the n base vertices that are mapped to true and, within each of the m triangles, the two or fewer vertices that are mapped to false. In any triangle having fewer than two vertices that map to false, include as many others (either one or two) that map to true in order to include in S exactly two vertices from that triangle. In total, then, S has as members n base vertices and 2m of the triangle vertices.

To verify that S is a vertex cover (i.e., for each edge in GF, at least one of its two endpoints is a member of S), consider that every edge connecting two base vertices is covered because one of those vertices is in S (namely the one that the assignment maps to true). As for the three edges within each triangle, that they are covered follows from the fact that S includes two vertices from each triangle. As for the edges connecting base vertices to triangle vertices, those connecting two vertices mapped to true are covered by the base vertices in S, while those connecting two vertices mapped to false are covered because S includes all the triangle vertices that are mapped to false.

Now we show implication from right to left (i.e., if GF has a vertex cover of size 2m + n, then F is satisfiable). First we observe than any vertex cover S of GF must include at least 2m + n vertices, because

Let S be a vertex cover of GF of size n + 2m. The observation above tells us that S includes exactly one from each pair of base vertices and exactly two vertices from each triangle.

Consider any one of the "triangles" in GF. As argued above, two of its vertices are in S, which covers all three edges internal to the triangle. Also covered are the edges from those two triangle vertices to their corresponding base vertices. But S, being a vertex cover, also covers the edge connecting the triangle's third vertex (i.e., the one that is not a member of S) with its corresponding base vertex, which means that that base vertex must be in S.

Our constructed assignment maps that base vertex to true, which means that the corresponding triangle vertex is also mapped to true, which means that the clause in F corresponding to that triangle is satisfied by the assignment.

Because the argument above applies to an arbitrary triangle, it applies to all of them. Which is to say that, for every triangle, its corresponding clause is satisfied by the assignment described in the construction.

End of proof.

Transitivity of polynomial-time reducibility: Note that polynomial-time reducibility is transitive. That is, if L1 is reducible to L2 and L2 is reducible to L3, then L1 is reducible to L3.

Thus, the two examples above demonstrate that SAT is polynomial-time reducible to CLIQUE. (One example shows that SAT reduces to 3-SAT; the other shows that 3-SAT reduces to CLIQUE. By transitivity of polynomial-time reduction, it follows that SAT reduces to CLIQUE.)

Definition: A language L is said to be NP-Complete if L ∈ NP and every language in NP is polynomially-time reducible to L.

Due to the transitiviy of polynomial-time reducibility, if L is NP-Complete and it is reducible to L2 ∈ NP, then L2 is also NP-Complete.

If we had some language/problem that was known to be NP-Complete, then it would open the door to showing, via polynomial-time reductions, that other languages/problems were also NP-Complete. But where do we get such a language?

Stephen Cook (and, independently, Levin) brilliantly proved that every problem in NP is polynomial-time reducible to SAT. Cook proved this by showing that for any nondeterministic TM M that runs in polynomial time, and for any input string w, a CNF E could be constructed, in polynomial time, such that M accepts w iff E is satisfiable.

The reason why the NP-Complete concept is meaningful is this:

Theorem: If L1 is polynomial-time reducible to L2 and L2 ∈ P, then L1 ∈ P. It follows that if any NP-Complete problem is solved by a determinstic polynomial time algorithm, the same could be said for every problem in NP, from which it would follow that P = NP.

For fifty years, researchers have been trying to either prove or disprove the equation P = NP, but no one has succeeded.